I’ve always believed that privacy is a boring thing to think about. Now, I just think that most discussions about privacy involved such vague and ill-defined notions that they become unproductive, and hence uninteresting. And for good reason — privacy, I’ve found, is a difficult conceptual knot to untangle, involving unusual but not illogical ways of reasoning.

Approached abstractly, the question Why does privacy matter? gives me nothing. I can’t say why, other than coming up with the uncertain, vague, and also very abstract notions of autonomy and freedom.

But it has become apparent that many specific topics I'm fascinated by are wrapped up with it. For example, I want to understand the implications of the concept of structured transparency and how it relates to other conceptions of information flows. So, in the last week I've found myself reading through various compelling ideas in this space, including Julie Cohen's What Privacy is For, Helen Nissenbaum's Contextual Integrity paper, Daniel Solove's Understanding Privacy and Charles Ess’s Digital Media Ethics.

One tl;dr is that privacy is about giving people space to negotiate their selfhoods, and different contexts with different privacy norms in which to exist; it’s also about shepherding good information flows. Throughout all these theorists’ works, heterogeneity and pluralism seem to recur as themes, whether it’s attempting to define privacy, the value of privacy, or how to enact privacy. I find this fascinating to noodle on, and will now attempt to take you through these ideas!

Shaky grounds

The unsteadiness of privacy as a concept has not gone unnoticed by any theorist I've read.

Many things have been or are conceptualised as privacy issues: fingerprinting, abortion rights, Google Street View photographing everyone’s front doors, X-ray devices that can see through clothing, companies collecting slightly more data on your browsing habits than they need to even if it’s all sitting in cold storage, your ex writing in a memoir about the details of your relationship and how it affected them, someone flashing you, public "anonymised" datasets that are in fact de-anonymisable, friends coming by your house at abnormal hours, end-to-end encryption, sex work, government background checks, and more.

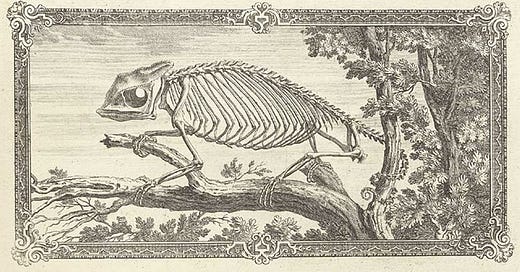

Privacy has been described as a “chameleon-like” word, and that’s probably why discussions about it have felt circular to me.

People have of course tried to define it, but resulting definitions have been criticised as too broad, too narrow, or simultaneously too broad and too narrow.

In Understanding Privacy, Daniel Solove says that traditional attempts at conceptualising privacy involve looking to articulate the unique characteristics of privacy, or finding a criteria that distinguishes privacy from other things. He categorizes (and diagnoses the ills of) six existing types of concepts of privacy:

The right to be let alone

Limited access to the self

Secrecy

Control over personal information

Personhood

Intimacy

I see the justification for each of these framings, but agree with Solove that no one of these approaches can explain the entire concept of privacy.

Solove argues, drawing on Wittgenstein's theory of family resemblance (which I highly recommend reading about!), that "privacy" in fact has no common core, but instead consists of a web of connected but distinct concepts. They have overlapping similarities, but no single common feature or consistent criteria. (Based on this view, he comes up with a useful taxonomy of harms related to—rather than a definition for—privacy, which you can see here.)

This family resemblance view helps explain why, while the concept still has significance and use, clear-cut boundaries for privacy are difficult to find. Privacy seems to have varied, but related, features and justifications.

This makes it hard to create a clean, accurate definition for privacy, and attempting to do so in order to understand it is likely a very messy, and not particularly illuminating process. So maybe we should back up and reason about the idea a different way. What are some reasons people care about privacy?

Privacy's value

At a high level, scholars generally acknowledge privacy as having both intrinsic value for its own sake, as well as extrinsic value of some derivative nature.1 The more intrinsic value view of privacy is generally linked to freedom, self-development, and creating intimate relationships with others. Extrinsically, it’s been said that it’s necessary for the sake of democracy.

(Before I continue, I’ll say that the scholars I read were mostly Western & English-speaking, and while I touch on cultural differences later, I haven’t gone very deep on non-Western framings.)

The purest (or most extreme) form of the argument that privacy is needed in democracy is espoused in classical liberal political theory. This prioritises individual autonomy and tends to view freedom as antithetical to community. The idea is that authentic self is essentially pre-social, and we need to protect and give privacy to that self, to retain an autonomous and thoughtful citizenry that can vote, speak and decide freely. Only morally autonomous selves can justify democracy.

Julie Cohen, however, pushes for more of a flexible notion of the self, one that can account for social and cultural influence and “relational, emergent subjectivity.” Her "postliberal" conception views selfhood as “malleable, emergent, and embodied” and dependent on people’s contexts and communities, rather than static and individualist. People are agentic and playful when it comes to figuring out how to navigate their varying social circles, what’s expected at school and at home, what parts of their environment they resonate with and don’t. And through navigating one’s environment, one creates who they are.

Even though we’ve gone from liberal to post-liberal, privacy is still important for selfhood:

Subjectivity is a function of the interplay between emergent selfhood and social shaping; privacy, which inheres in the interstices of social shaping, is what permits that interplay to occur. Privacy is not a fixed condition that can be distilled to an essential core, but rather “an interest in breathing room to engage in socially situated processes of boundary management.”

For her, privacy shelters subjectivity from “the efforts of commercial and government actors to render individuals and communities fixed, transparent, and predictable.” Less privacy means less space for self-making, for shaping and understanding the boundary between one’s identity and the wider social world.

This conception is less absolute than the liberal conception of selfhood; it’s more about letting there be negative space, creating "play in the joints".

Cohen coins the term “semantic discontinuity,” which she takes to be the opposite of seamlessness. Semantic discontinuity “helps to separate contexts from each other and preserves breathing room for personal boundary management and for the play of everyday practice.” I interpret this as non-interoperability, impediments to information flow, unevenness in the landscape of disclosure. The preservation of loosely connected spheres between which information does not flow seems critical to a felt sense of privacy.

It seems clear that we need privacy so that we can have a sense of ourselves and our plural identities and so we can vary our selfhood in different spaces. Perhaps a definitive trait of self-development is experiencing oneself as fluid multitudes that vary across contexts.

There seems to be a deep connection between privacy and identity which is noted in Cohen’s piece. Lucian Floridi argues that one would say "my information" not in the sense of possession or ownership of a thing external to you (as in "my car") but in the sense of constitutive belonging (as in, "my feelings"). Personal information is something that people hold close to who they are. Privacy is not just about personal information — a person is not identical to all the information you could possibly gain about them, all the data they generate — but the idea points at some enduring link in all the readings between privacy and selfhood.

In different cultural contexts, how people see their identities is linked with privacy norms. Where there is a a strongly individual conception of self, protecting an individual’s private life is widely accepted. Cultures with a strongly relational conception of self (e.g. cultures that center Confucianism or ubuntu) usually see individual privacy more negatively, insinuating that the person has unscrupulous things to hide.

In the more relational cultures, however, Charles Ess posits that “the boundary between groups may be less permeable to information transfer”. In other words, maybe the intimate circle is simply larger, rather than perhaps what Westerners would perceive as nonexistent; there still exists a privacy boundary between your community and strangers. There may, across varying cultures, exist a concept of some inner sphere(s) vs. some outer sphere(s), wherein identity depends upon negotiating what is inner and what is outer.

Contextual integrity

Helen Nissenbaum's idea of contextual integrity is useful for clarifying Cohen’s idea of having multitudinous selves in different, disjointed contexts. It also feels particularly apt for thinking about privacy in digital spaces.

To Nissenbaum, in all areas of life there are context-dependent norms of information flow (emphasis mine):

Observing the texture of people's lives, we find them not only crossing dichotomies, but moving about, into, and out of a plurality of distinct realms. They are at home with families, they go to work, they seek medical care, visit friends, consult with psychiatrists, talk with lawyers, go to the bank, attend religious services, vote, shop, and more. Each of these spheres, realms, or contexts involves, indeed may even be defined by, a distinct set of norms, which governs its various aspects such as roles, expectations, actions, and practices. For certain contexts, such as the highly ritualized settings of many church services, these norms are explicit and quite specific. For others, the norms may be implicit, variable, and incomplete (or partial).

Contextual integrity is satisfied when norms of appropriateness (what information about persons is appropriate to reveal in that context) and norms of information flow or distribution (governing how information moves between parties) are upheld.

For Nissenbaum, the complex idea of public surveillance needs the framework of contextual integrity. Why does it matter if Google Street View takes images of your home and hosts them on Maps, if anyone can walk up to your front door and take a photo of it and effectively get the same information? In public spaces, nothing is private, right? Well, the issue is that Google Street View violates norms of how knowledge about your home should be appropriately distributed.

I’ll digress and say that for digital spaces, it seems fairly unclear what is appropriate to reveal and how information should move between parties. Opacity and complexity make it hard for users to understand how/what information is transmitted, and the internet is a newly constructed context with very different dynamics to the physical world. Many norms are being made up as we go, now. Nissenbaum does say that she isn’t advocating for adjudicating privacy purely on the basis of what is normal and expected.

Cohen and Nissenbaum both recognise the existence of different spheres and context in which privacy is negotiated. Nissenbaum talks about the existence of qualitatively different norms in each space, whereas Cohen more emphasizes the need for disconnect between different spaces. Nissenbaum is more inclined in her analysis to hold norms constant as a variable and focus on what it means to uphold them; Cohen attends more to the unsteadiness of boundaries, the negotiation between self and other that happens in any given context.

Nissenbaum, draws a lot upon Michael Walzer's idea of “spheres of justice”, which is similar to Cohen’s notion of semantic discontinuity. These spheres are distinct, separate regions for which norms vary:

Walzer develops a theory of distributive justice in terms of not only a single good and universal equality, but in terms of… complex equality, adjudicated across distinct distributive spheres, each with its own, unique set of norms of justice.

For Walzer, "complex equality, the mark of justice, is achieved when social goods are distributed according to different standards of distribution in different spheres and the spheres are relatively autonomous."

I haven't read Walzer, but this brief definition of complex equality seems to make it hard to figure out any standards of justice. “Things should be different in different places” doesn’t help you figure out when something is going actually, terribly wrong in one place. However, taken in the context of Solove, Nissenbaum and Cohen’s analyses, we can see the need for these differing spheres, and we now have conceptual tools for adjudicating their impact on privacy. How connected are these spheres? Is contextual integrity is upheld? Do people have breathing space for self-other boundary management? Are any of the harms in Solove’s taxonomy applicable?

Privacy and pluralism

A person’s demand for greater privacy is not always for noble reasons; obviously there are harmful reasons for trying to keep things private. But privacy is not just about letting people have secrets; as said above, it’s about giving people space to negotiate boundaries, and about shepherding good information flows.

Recently I’ve been thinking about what social conditions bring forth pluralism. I live in a liberal society where we encourage differing beliefs in the abstract, but how do we actually concretely get people who believe in different things earnestly and thoughtfully?

There is no simple answer, of course, and this intellectual foray into privacy is limited. But privacy seems essential to pluralism. Privacy is not only pluralistic in its meanings and components—a family resemblance concept that, when you look closely, is actually a multicellular organism—it also encourages pluralism.

If people can exist in more and disjointed intimate spheres, they can create more distinctive selves. If people have the space to try new things, don a slightly different persona when they meet a new person, indulge in hobbies seen as uncool or lame, perform on a stage to strangers, test the Overton window with trusted friends, and learn from these actions without having everyone know about it — it creates a bulwark against homogeneity. As a society, we become more plural in our many characters. And so does each person.

People say that privacy or surveillance only matters if you have something to hide. But getting rid of certain kinds of privacy embedded into our social fabric may smooth out any distinctiveness of self, and preclude the possibility of having anything you might want to hide at all.

I have many thoughts about privacy from the last couple weeks of reading that I’ve left out, so there probably will be more posts about e.g. What happens when we unbundle traditionally bundled information? Is there always a person to which a piece of data belongs, and if not does it mean it is “up for grabs”? What happens to digital privacy when our inference tools get really really powerful? And so on. I’m also now fascinated by the Wittgensteinian idea of family resemblance and might apply that hammer to more nails. Alongside this, I’m slowly working my way through a cryptography textbook, and hope that I can begin to integrate these two kinds of study more!

Honestly, I am not completely convinced that “intrinsic value” is a coherent concept, and would love to read more about this. For now, let’s just say that there’s some continuum along which some things tend to be valued for its own sake, vs. valued for the sake of something else that is good.

Really loved this! When I think of privacy in the basic sense of our digital identities, the 'pluralism' you defined seems very relevant. What would it be like if people could see our full online/offline existence in one place (since the data already exists)? What happens when our employers can see it? What happens when it is searchable? etc.